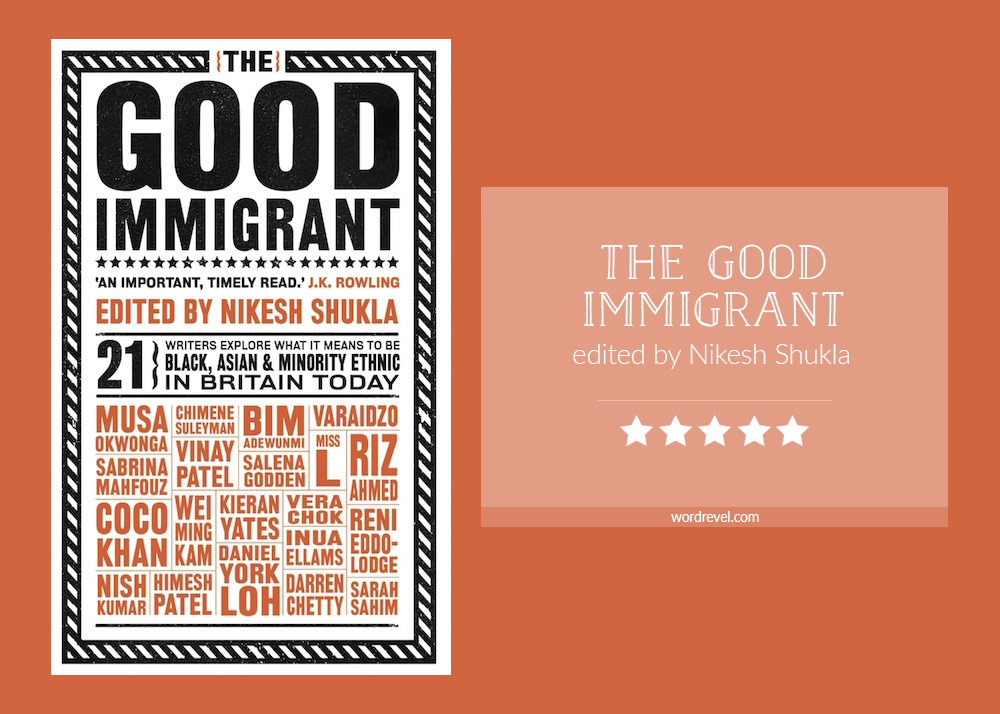

The Good Immigrant by Nikesh Shukla, Varaidzo, Chimene Suleyman, Vera Chok, Daniel York Loh, Himesh Patel, Nish Kumar, Reni Eddo-Lodge, Wei Ming Kam, Darren Chetty, Kieran Yates, Coco Khan, Inua Ellams, Sabrina Mahfouz, Riz Ahmed, Sarah Salim, Salena Godden, Miss L, Bim Adewunmi, Vinay Patel, Musa Okwonga • contains 254 pages • published September 22, 2016 by Unbound • classified as Race & Ethnicity, Sociology • obtained through purchase • read as hardcover • shelve on Goodreads

The Good Immigrant by Nikesh Shukla, Varaidzo, Chimene Suleyman, Vera Chok, Daniel York Loh, Himesh Patel, Nish Kumar, Reni Eddo-Lodge, Wei Ming Kam, Darren Chetty, Kieran Yates, Coco Khan, Inua Ellams, Sabrina Mahfouz, Riz Ahmed, Sarah Salim, Salena Godden, Miss L, Bim Adewunmi, Vinay Patel, Musa Okwonga • contains 254 pages • published September 22, 2016 by Unbound • classified as Race & Ethnicity, Sociology • obtained through purchase • read as hardcover • shelve on Goodreads Synopsis:

How does it feel to be constantly regarded as a potential threat, strip-searched at every airport?

Or be told that, as an actress, the part you’re most fitted to play is ‘wife of a terrorist’? How does it feel to have words from your native language misused, misappropriated and used aggressively towards you? How does it feel to hear a child of colour say in a classroom that stories can only be about white people? How does it feel to go ‘home’ to India when your home is really London? What is it like to feel you always have to be an ambassador for your race? How does it feel to always tick ‘Other’?

Bringing together 21 exciting black, Asian and minority ethnic voices emerging in Britain today, The Good Immigrant explores why immigrants come to the UK, why they stay and what it means to be ‘other’ in a country that doesn’t seem to want you, doesn’t truly accept you – however many generations you’ve been here – but still needs you for its diversity monitoring forms.

Inspired by discussion around why society appears to deem people of colour as bad immigrants – job stealers, benefit scroungers, undeserving refugees – until, by winning Olympic races or baking good cakes, or being conscientious doctors, they cross over and become good immigrants, editor Nikesh Shukla has compiled a collection of essays that are poignant, challenging, angry, humorous, heartbreaking, polemic, weary and – most importantly – real.

Initially I meant to write a pure book review, assessing the merits of The Good Immigrant. Considering how much of my own existence is reflected in these essays, I felt compelled to go beyond that.

I wanted to explain why this book matters so much to me and reflect on some things that particularly struck me. In fact, this book made me want to write my own essay in response but I’ll save it for another time. For this post, my focus still is this book that struck a million chords with me, though I’ve added some anecdotes that tie in with my reflections.

The Importance of this Book

The Good Immigrant is one of those books that should be required reading to better understand the world today. More and more people migrate, seeking better opportunities abroad. This causes friction with locals who fear that foreigners take away their jobs. Some are wary of foreigners who don’t speak the local language or don’t share the culture.

Even though the UN reported a staggering 244 million migrants in 2015 worldwide, xenophobia is on the rise as well. There is a lack of understanding, which makes it difficult for some to accept immigrants. I think The Good Immigrant contributes to bridging that gap not just within the UK but for other countries too.

Structure of The Good Immigrant

Altogether there are 21 essays penned by writers from diverse cultural and religious backgrounds. What ties them together is that they all live in the UK. They have very different experiences but largely agree on one thing: they’re often regarded as the “Other”. Their skin tones, their speech, their clothes, and so on set them apart, making their efforts to assimilate tenuous, even if for some, British is the only national identity they lay claim to.

Each essay relates experiences from the respective writer. They explore the multiplicity of their identities, underscore prejudices they have faced, recount their efforts to fit in and reflect on what it means to be treated as a foreigner even though they might consider themselves local:

“You need to know this. Because of your skin tone, people will ask you where you’re from. If you tell them Bristol, they’ll ask where your parents are from.”

— Namaste, Nikesh Shukla

Since these essays are based on experiences, they are deeply personal. They speak to the reader, reminding them that immigrants are more than statistics. They are humans, no more, no less.

A Note on the Contributors

When I picked up The Good Immigrant, I expected narratives from a more varied sample of British immigrants. Nikesh Shukla admits in his editor’s note that he chose contributors whom he knew. The majority of them are active in the creative and entertainment industries. With a general title referring to the immigrant, I didn’t quite expect that. I recognised too few names printed on the cover. Anyhow, each contributor’s voice was significant to the book, regardless of their professions.

My Personal Connection

Mixed Ethnic Descent

As an immigrant of bi-ethnic descent living in a multicultural society, I connected very deeply with The Good Immigrant. So many thoughts, questions and doubts were familiar to me. I grew up with those and live them every single day. Details vary, of course, but at the core, I know that these essays contain truths that not everyone recognises until they too are faced with such realities.

“She was right, of course. As a term, mixed-race could never fully illustrate my experiences. It described nothing; the act of being not one thing or another. To be a mix of races is to be faceless, it implied, and yet that had never been my reality.”

— A Guide to Being Black, Varaidzo

Being a child of mixed race is confusing. You’re one race but also another, you’re neither and yet you’re both. Sometimes I don’t feel Filipino enough because I don’t speak Tagalog but then I remember things that have defined my ethnicity that way.

Food

My mother told me a few weeks ago, laughing, that she recalled time when I was still in kindergarten, I had friends over. Like any good host, we served food — ginataang bilo-bilo, to be precise. This dessert is made of glutinous rice balls in coconut milk.

While I happily ate my favourite food, everyone else struggled. The other (French) children had difficulty with this sticky mess, unable to swallow the glutinous rice balls. My mother had to remove the ginataang bilo-bilo from the table and serve something familiar instead.

Little things like that add up. Food is a significant part of culture. Tastes aren’t pre-determined. They’re taught as part of children’s socialisation. Just as I reach for soy sauce, others ask to pass the salt to season their fish. My staple food is split between rice and bread but I can make do with potato. I don’t care for chilli but depend on ginger to spice dishes. I love mangoes as much as I love cherries. My food choices show a distinctive mix of cultures.

Confusing Race

Due to my mixed ethnicity, many people struggle to categorise me. Over the years I’ve learnt to code switch. When I speak with the local accent and communicate in Singlish, I’m often mistaken for a Malay person. That confuses interactions because here in Singapore, Malays are generally brought up as Muslims. Going back to food, that means eating pork is forbidden.

I once ordered clam chowder. The sales person helpfully informed me that the chowder contained bacon. I told them I was aware of that. They repeated themselves, “There’s pork bacon in it.” I said it was fine and proceeded to the cash counter. When they handed me the tray, they did so very hesitantly.

“The only thing worse than racism is inaccurate racism. It was hurtful to me and to the people who are actually Muslims.”

— Is Nish Kumar a Confused Muslim?, Nish Kumar

This incident I mentioned isn’t one of racism but rather speaks for cultural sensitivity. They thought I was Malay, assumed I was Muslim, and therefore didn’t want to serve me food that wasn’t halal. Nonetheless, this shows how important race is in our interactions. It also is a perfect example of how confusing it can be. Race isn’t always easily identifiable. On the flip side, it’s bewildering when the expectation to practice a culture that isn’t yours to begin with is hoisted unto you.

Home

“To be an immigrant, good or bad, is about straddling two homes, whilst knowing you don’t really belong to either.”

— Forming Blackness Through a Screen, Reni Eddo-Lodge

This line is surely one familiar to anyone who has lived abroad for an extended period of time. Particularly when a migrant is young, they don’t have a chance to grow deep roots in their home country. Second- and third-generation immigrants too might struggle because even though they’re born in one country, they have relatives in their parents’ home countries. Both places raise a sense of belonging but neither is entirely complete. How do you split your person to call home a singular place?

Thank you for sharing this book! This is the first I’ve heard about it, but I’m definitely going to read it now. Thank you also for sharing personal stories about your identity – I can relate to them, but it still makes me sad to hear them. I have a Chinese background (but have never been to the country and speak the language very badly), but was born in Indonesia and have been calling Australia home for a couple of years, so the concept of home and belonging is definitely one I’ve been pondering for a while.

I’ve been hearing a lot of excellent things about The Good Immigrant! It was lovely to get all your in depth thoughts on this essay collection, and I truly think it’s something I will enjoy and benefit from as well when I finally get a chance to read it.

I haven’t heard of this before, but I will definitely be keeping an eye out for it. It sounds like such an important collection of essays, especially here in the US with our current political disaster :P

Cool review. Thank you for sharing about this book. I probably will add it to my TBR. It seems interesting read! I have experience similar to you. I am from Indonesia. My father is Chinese descendand and my mother is Sundanese. My physical is like chinese. I learn to code switch, too. In sundanese, I will act like Sundanese and answer that I am Sundanese. But In chinese neighbourhood, I will admit that I am chinese. I am muslim and in Indonesia,most chinese are non muslim and I often mistaken as non muslim. They often surprised when found me go to mosque. But It did not happen anymore since now I wear hijab/veil. :)